An interview with Sofia Bustamante award winning social innovator

….. talking about her journey in social innovation and the books which led her there

Social Innovation

Sofia: One is, I came across an architect who says, you know, she creates buildings that breathe, Mary Oxman, and I really respect her work. And she sees buildings as a process rather than objects. She sees architecture as a process, and I went oh my God, because I see life as a process, you know? Rather than the sort of forms. The processes generate the forms. And she says nature generates processes that generate form. And I was thinking wow, because that’s what the, you know, like facilitating and that kind of thing, you generate processes that generate certain outcomes, like very specific forms. You know, like ideas, adventures, different states of being in a group, etcetera. And that always comes from sort of understanding people as a system, you know, living systems and interactions as processes. So sort of looking at everything that way, then … kind of can generate any kind of outcome, you know, it just needs the right context and the right stimulants. You can really have more creativity, less creativity, more conflict, less conflict. You can generate any sort of state or outcome in a group.

Sorry, am I moving a little bit much? I was really excited, but then, I was in Geneva and I was at a point where as I said, you know, I was getting respect for what I do and finally sort of getting paid for it. It was quite funny, because only when I get paid that my Dad actually took what I did seriously, you know. He said, what are you doing? I said I'm doing this piece of work, it was for the UN at the time, and he went, oh, what is it you do? Because you're being paid. What is it you do? Oh, that’s great. I was thinking, this is what I’ve been trying to do for the last ten years, but there you go.

So it was interesting, I sort of became aware, certain things that are only seen when they’ve dressed up in a certain way. You know, things are only seen when money flows through them, and other things are only seen when they're a thing. They're not seen when they're a process. So, if you just bear that in mind. Basically, I met this woman and she came on to the bus, and she had sort of leathery, weathered skin. She was smoking and she had that sort of like, lived look. And we really clicked straight away and we were talking. And she was kind of in the Sarajevo sort of conflict. She was out there, she was working for the UN and she was doing sort of missions out there, and … because of the conflict. And she said, oh, … I told her what she said … She said oh, you're one of those people, you get people to talk, don’t you? Yeah. It doesn’t work. And she says no, basically, the only thing that I’ve seen work is where you get, for example, two people, two different kinds of people in a shared economic context having to work with each other, for example, the Serbs and people in Kosovo, and that created economic harmony and shared economic output.

All the talking does nothing. And I felt this … I could see where she was coming from and I had to respect what she was saying. But I sort of realised, OK, this is another thing, it’s like people only really see things when they produce hard outcomes. They're not going to really value the soft outcomes until those soft outcomes in some way produce the hard outcomes. So it’s sad, but that is the state of affairs. And I thought OK, so what I need to do is, I need to start the other way round. Rather than trying to persuade people that look, with all these soft outcomes you get really good hard outcomes. I had to just go for producing the hard outcome through these soft processes and then at some point, people go oh, how did that work then? And I’ll go oh, it’s all the soft things, they're the real reason.

And so with London Creative Labs, you know, I got really inspired by Grameen -

Sofia: - Sure … and I went to look actually at what were the soft, the underbelly of his work. And interviewed the women there, and I saw that Grameen was really 25,000 hubs of 60 women that self-organised, you know, their branches. And I saw they basically had ironed out all the different conflicts because they were so … there was no mission drift, and that’s why they’d scaled. I was thinking yeah, these hard outcomes have come because of certain processes in place. Muhammad Yunus, he won a Nobel prize because he started off microfinance. Yeah, in the poorest urban settings. He lent $27.00 to 42 people and … Because he was an economics professor and he was thinking why did none of my theories have any relevance on the life of these extremely poor people around? And so he asked them what’s the problem, and they didn’t own their means. Yeah. They didn’t own their own tools and so they were totally in debt. So he lent them some money. They all paid it off. You know, they were all solid and he thought, wow, they're motivated, they're going to be credit worthy. So then it went from strength to strength and he basically started a whole bank that way, to give to people didn’t have any credit, or collateral. And the bank got stronger and stronger. And you know, in the crash, in 2008, is one of the few banks that wasn’t affected in the slightest. So it’s very solid.

Bushra: So you went and interviewed … ?

Sofia: Yeah, I interviewed the people behind it and I saw that whatever their mission was to help the poorest of the poor, to better their lives, and, through microfinance. And through becoming an entrepreneur. Everyone can be an entrepreneur. That was their belief. And so they basically just removed all the obstacles that would stop anyone being an entrepreneur. And so with women, they would go to women rather than expecting women, you know, in the villages to come to them. They’d go to the villages, they’d go to the houses. And they got to a point where women from being in a place that they wouldn’t touch money, felt like they couldn’t, they’d bring the men in the village on board and they just did what was necessary to enable women to handle money, to handle their own money, to be trusted by themselves, by their husbands. So through, basically, Grameen and B, another organisation that did this work with a … they were clear what they wanted to do and then they used that as the guiding line when difficult decisions came up. So they stayed true to that. And over 40 years that’s really impressive. So for example, when someone dies, a borrower dies, normally if a bank is just after profit, that debt would get passed on to a family member or something like that. They decided to cancel the debt in that case because they said if it gets passed on to the family, that’s going to cripple the family. And our aim is to better communities and better the situation of poor people. So, you know, they had to save. If they were borrowing they had to save. So they used all these nudges to nudge the culture in the direction after nudge after nudge and then they really enabled basically a different culture to emerge. So that was amazing.

Bushra: So you were looking at the hard outcome?

Sofia: Yeah. So I got back to the UK and I said OK, and I thought OK, what’s a hard stuck problem? And I thought, well, unemployment. You know, if you’ve got generations of people that have never been employed. And in communities you’ve got multiple issues of deprivation going on, so I thought OK, let’s just look at work creation. And like Muhammad Yunus, you know, it’s like creating jobs rather than just, you know, filling more jobs. And I thought, where do jobs come from? They come from small businesses, locally, organically grown small businesses generally are sort of the engine of the economy, actually. I thought, what about small business based, and I was thinking about Grameen where they have self organising, so they avoid unnecessary competition. There’s competition there, but they avoid unnecessary competition because of that self organising and … so the marketing costs are lowered. And I was thinking, well, what are the needs that these businesses are going to serve, and who gets to say what those needs are? And I was realising, well, it depends who’s in the room. So I have to get into the room, everyone, and make sure that those people that wouldn’t usually get there and to make sure to get them there, you know, so we’d put most of our marketing budget on the hard to reach, because that made sense. And we targeted all the sink estates, with a very specific leaflet and I remember 18 different versions to get it right and make sure it will reach people on the sink estates. You know, emotionally and perceptually. And they then came, and I realised well, it’s no good actually if they just come because if they are in themselves feeling completely disempowered as a habit, as a way of life and no identity, they can be next to people and they're not going to participate meaningfully, so –

Sofia: Yeah. So thought OK, what do we need so that they can? And so basically I just devised something called The Skills Camp, which was a sort of combination of a bunch of things. But the aim was to actually help them to step into their purpose and show up from that place, basically. And help them feel that even though they might have much less qualifications, they can be next to a Harvard graduate and feel equal on some level, you know. That was the idea. And it worked. So we put them through the Skills Camps and it was amazing, it was a really intense process, amazing. And when we ran the final event where, you know, you have everyone from the community and the social start up labs, you know, everyone handing their own data and saying what businesses are needed, you know, what opportunities are here and then gathering people round the opportunity, using business model generation, people could come up with something there and get them into … We had these action circles things that would help them take one action immediately and, you know, get the whole thing moving. So from a huge expanse, it actually went in a direction involving people and people got a different picture of their local area, etcetera and what they could do.

And those people who participated in that, in the Skills Camps, the hard to reach who had gone through that other process showed up, there were the most … active.

Sofia: - constructive participants in the room. And they really stood out. And it worked, you know, to bring them in meaningfully. And then it worked also to identify new opportunities in the room and for people to get a sense that actually, this is, you know, their community and the economy means them, they are the economy in a funny way, like people is economy. And what they do influences it. And jobs come from, actually we create jobs. We can create jobs and we can be job creators rather than having that feeling of being done to, which I really just felt so many communities just feel done to.

So that was one element, you know, that, and it really worked and it was great, got recognised as well. And really it was a hypothesis, it was proving hypothesis that if you include more people in the economy, it’s richer and that you can include people. That people can participate meaningfully no matter what their background. So yeah, that was … all those designs was the soft stuff. What they came to was a thing, the social start up lab or the Skills Camp and then what came out of that were ideas, fledgling ventures, new connections, and we tracked all of that. So the local council were really excited about it and, you know, it was common that we’d stop in the street and the deputy leader would say oh, it’s fantastic, how much are we funding you for that? And we’d say not a penny. Because they wanted to but it didn’t really, they didn’t … it was so holistic they couldn’t see it, in a funny way they couldn’t see it. They felt the benefits of it and we had people at our graduation ceremonies and, you know, really bigging it up but they couldn’t find a way to plug into it. and unfortunately, the people who did find us were a huge, you know, conglomerate, J P Morgan. And I say unfortunately because I would have loved it to be local, you know, much more local. But J P Morgan saw the holistic aspect and just went right, come to Canary Wharf tomorrow. And within 48 hours we’d signed something. And that made me think that it’s really difficult when things aren’t seen, and it’s like, how do people see things? What are the signals that make them think something exists and other signals that would make them not think that the thing doesn’t exist. It’s like that cognitive dissonance thing. And it’s quite interesting.

Bushra: And the future, what do you think about –

Sofia: So, yeah –

Bushra: ...the skills that do not have the soft inputs with the hard outputs and the thing, and the –

Sofia: Yeah. So I have a sense that, we will … Yeah, there’s a literacy about being able to read the inner processes and be able to then actually play with them, design them, and track them and understand them. And you can see this starting to happen with the notion of the quantified self. So you’ve got the technology being used to help people get feedback and understand these key signals and data from the inner world. You know, even like people’s breathing rates and people can understand what wellbeing actually means, what it looks like and then people will understand actually what the cause of it and how, you know, how you’ve got these kind of esoteric notions of spirituality, meet this weirdness of hard … basic needs of economics and then the sort of social elements of status and all that. And all those things have a reason, like this thing of … I know there’s a reason for all these things and actually, I think technology would little by little catch up and help people to navigate that and basically design really different states of beings much more directly. So sort of managing our inner state.

I think there’ll be a lot more of knowledge, basically, common knowledge about how to do that and technology will enable that a lot more. I think that also we will start to understand things like what is psychic. Those sort of abilities. What do they call this? Siddhis they call them in yoga. You’ve got the Siddhis, you know, high levels of meditation enables people to do kind of extraordinary human things. Well I think that will become more common and for people to be psychic will be much more understood and accepted. And we’ll have not only technology to actually prove some of these things, but you will be able to train much more, there’ll be like common curricular understanding of how we do that, as an individual and then as groups. And that notion of identities, I think we’ll be able to actually track our identity across people. So there’s an identity that comes, you know, not just my identity but our shared identity. And we’ll understand that more as a sort of living thing in its own right. And we’ll kind of include these identities, you know, like the spirit of this place, the spirit of this time. These spirits will be actually understood as a kind of a swirl of consciousness, if you like, that maybe exists across time in a different way.

And I think there’s this notion of veils lifting between things that we don’t usually connect up. I mean, there’s an acceleration of technology in different areas that is insane that the moment. The virtual reality and artificial intelligence. I was just speaking to a friend yesterday, Pam. So I think for example imagine a conference where you can track, you know, you can see the motivation in the room mapped by second and understand how things are influencing things across a big group of people. I think basically that sort of barrier between mind and body is going to dissolve a lot. I mean there’s already an understanding that the body is the subconscious mind. So that sense of the difference between the inner and the outer realm, the relationship with the two, I think, will be much better understood. Orders of magnitude of difference for that human being.

Bushra: And in terms of what projects you're doing at the moment?

Sofia: OK. So at the moment I'm working on … the main one that takes up my time at the moment is the Listening Café. The Listening Movement. This was noticing after the Brexit vote that the quality of debate was really depressing for most people. I mean, if you talked about politics, people mostly would respond -

Sofia: Depressed. And also, a lot of my own friends were showing signs of anxiety. Ones that wouldn’t normally do that. And then people approached me in that week after Brexit, saying what are you going to do because you work with dialogue. People from the States who sort of remembered my work from before and were saying hey, I know someone that was banging on about this stuff like in 2009 and then saying look, now is your time. And I actually at the time was really geared up to do something else but I felt that calling, like when I did for London Creative Labs and I thought OK, I’ve got to do something. So I thought what’s the most simple thing I can do? And I thought well, the thing is at the moment, is perception of safety, of wellbeing, of, like, aren’t we safe and these people that think differently, whoever they are, are threatening us. That was the common rhetoric. And that is so dangerous, it’s so … unnecessary and unsettling.

Sofia: So I thought what’s the way to address that? And I said OK, help to overcome a sense of other … Just overcoming that sense that this person is like a different species. And I thought how can we do that? and I thought, well, you know, actually, if you set the conditions that people can connect with the other person’s humanity, then that sense of other is overcome.

Sofia: OK. And I thought, OK, a good conversation can do that. So really it was actually to give people. If someone was in a context where their family think really differently to them, it feels dangerous to say what they think. And I heard that this was causing stuff between couples, you know, between big financial institutions that were disagreeing with each other, there was a real, real tension and stand off in that situation. I thought, give people a good experience of conversation where they actually feel really heard. And they actually get to listen from a different place. Then there’s a chance that we can connect as human beings and you know when you're going to get that connection you really feel close to someone because of a conversation, it’s just amazing. You feel connected and you physically physiologically feel more relaxed and safe. And I thought that’s just lovely. If people have that, an experience of that rather than being preached at, oh you need to listen, just give people experience of being listened to and then they’ll want more of it and give people also the chance to feel that listening to other people is safe. That’s what this is. Basic idea was small groups, three people listening, one person talking, each taking turns to be heard and getting a chance to be heard without prejudice, being able to speak without having to perform. And without having to try and persuade each other. So it’s really nice when someone listens to you without trying to persuade you. And often actually we’re most persuasive when we’re not trying to persuade anyway.

So that was the idea. Very simple set up, invite people and have that. I thought the idea of just having a little coaster in the middle with the basic principles of listening that people then could take away. The idea was that it’s a very, very little step in to practice conversation as a tool, and the art of conversation. I sort of realised, you know what, it’s something that we’re not taught and … it just can make so much difference.

Bushra: How many sessions have you done so far?

Sofia: We’ve done August, September … we've done three listening cafes. So they turned into a café where you get many groups, in the room.

Bushra: How many people are coming?

Sofia: Well, it’s small groups. We’ve had about … Each listening café we’re getting about ten people. It’s just a really intimate atmosphere and the thing in itself is really working and what happens afterwards is we get, you know … We had four hours of conversation after the first one. We had a two hour café and then four hours of conversation. But we’ve had a lot of people who want to come along and who’ve expressed interest in support. So it’s been sort of an inordinate response from the community and with people sort of asking for it to be brought into their sort of organisational set up. We’re talking to someone who works very closely with the NHS and who is saying about the need for doctors to listen to each other and have that experience, because they don’t have those places where they really can hear each other and be heard. And this would be really good for that. So there’s the idea of somehow to gradually bring that in. And then someone from the Listening Café said oh, I’d like to do some work in Streatham with homeless people there.

For example, we’ve got people in other towns, in Sheffield and Hastings that are sort of waiting to get support to help run their own listening café. So we had one, on World Listening Day, the world’s first Listening Day on 21 October just gone. Someone ran a Listening Café in Australia. And that was really nice to see, there are people who want to do them in the States. So there are sort things that will happen, in small groups of people, unless it’s something that’s got a lot of, you know, sort of a big name behind it and funding a large scale big café. It’ll be a café of a few groups of people around tables, you know, a kind of cosy setting. And just having that really healing experience of being with other people and being able to be nothing but human. So whatever you talk about, it doesn’t have to be interesting. You are there … When people don’t try to be interesting they're usually much more interesting anyway. And it’s actually practising that art, kind of like a lost art of listening. Listening as individuals, listening as a group. And the big sort of well up of good feeling that comes from that is, you know, it’s been a sign that, yeah, it kind of needs to happen. So yeah, that’s the Listening Café.

But we’re sort of linking up with other movements that are emerging around this same need. The empathy circles that Edwin Rutsch runs in the States. Sidewalk Talk, that take therapists out onto the street, really as a provocative statement. And then there are other movements like Tea With Strangers and there’s something called Seven Cups. And this is all about help … If you think about what The Samaritans does, The Samaritans, you know, are kind of like people who … closed and may be feeling suicidal can ring up and talk to somebody. Well this is kind of bringing it more into the light a bit more. And I love The Samaritans, I think what they do is fantastic and they’ve kind of been there since a long time. And what’s needed is where it can be, I think, even more visible, that we have place and spaces where we can be human with each other and we are not valued according to our productivity and according tour financial assets and according to our aesthetics. We’re just valued for being human. And safe in that valuing. And in a way that we can actually kind of rely on it, as in it feels stable, it doesn’t feel like this weird thing that is just sometimes there for us and mostly not.

You know, I think people’s sense of safety comes from emotional safety actually. I’ve seen enough surveys done about very wealthy people, for example, in Switzerland, you know, 70% of the wealthiest Swiss businessmen feel financially insecure. That’s kind of miserable. That’s a bottomless pit, really, of something that’s being used to cover up something else in away. So it’s that wellbeing, basically. And as an antidote to depression, to anxiety, to kind of the rising situation of mental health that's coming from not really being able to navigate the pace of change. The loneliness of the result of our political systems. And the sense of people being against each other, you know, we have to compete. All those things that we've talked about in so many different ways, so many different places. But they're really coming into effect. So we need antidote.

There’s a consensus reality of what we all know that we all know is happening, and when that matches what you feel, so when you feel healthy, you don’t feel like there’s a schism in your brain going on, you know. But when they say we’re a very positive company that really values its people, and basically their actions don’t, yet everyone goes along as though they do, right, all the talk is double talk. double speak. It makes you mentally unwell. It’s really, really unhealthy in that environment. Because you're basically having to lie, you know what I mean? And you know that you're having to lie. And you have to push that down, it’s horrible.

Another idea that came up I’d love to share with you, it’s not something I'm necessarily do anything with but I want to share something with you. OK. So, and this is just coming out of my own recent self. And was saying to me, you know, this is really revolutionary. It won't be obvious, right. OK. So I grew up in a family unit that had dysfunction. Welcome to the world, most families have dysfunction, you know what I mean. So spent a lot of time sort of resolving those conflicts, and therapy, all the different modalities to, you know, to be able to have good relations with my family and to support them as well to do that. So, you know, that’s the individual family unit. But I sort of realised quite late that I’ve done a lot of work on myself and I know that I will for the rest of my life. I believe that the more you look into the mind, the more there is. It’s just -

Sofia: Sorry? There is another factor beyond the immediate family unit. And, you know, I look at these lost youth, people who have had, in a way, there's a lot of debt of investment in those people, as in they haven’t been invested in. So you see, you know, people from a public school who’ve had thousands and thousands of pounds of investment and have access to networks, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. And, so -

Sofia: So a lot of the time it’s kind of like the community facilitation of integration of a person to discover their appropriate fit and purpose is way beyond really a school, or the immediate family unit. Really ideally and I'm not saying this is common that it happens ideally but ideally the community, the wider family, the healthy integration of the nuclear unit with the wider family and then the wider family in society would facilitate a person to sort of zig zag through these connections into who they're being. And actually, I think of it as social chi flowing. So you know like in a body, in our system they’ll cut off this and they’ll cut off that, they look at this wrist or they look at that. If you go to a Chinese doctor, they’ll say how are you? How is your period? And you think what’s my period got to do with anything? And it’s like, you know, how are you sleeping, what’s your stress level? And they come to it in such a different perspective. It’s like they look at all the white space, not just the dark space, the form, but they look at the space between the form in your system. And they really look at … is the energy flowing in your system as a whole? And then, I thought, well actually, in society people who are very isolated, in the way I thought this idea of social chi. Like, there's the energy of interconnection for them in society just isn’t flowing. And the energy gets really stuck, like in a pool that’s like a swamp.

So in a healthy system you get this social chi flowing into the person, between the person and the family and the wider community. If there aren’t blocks. And because of economic pressure and because of, you know, especially for economic migrants, you know, my Dad was an economic migrant. So a lot of the time he felt afraid of letting his daughters out, so I kind of wasn’t really allowed to socialise properly as I was growing up. I was controlled to the last minute. I want to go to a party, at what time, he’d come into the party and take me out. It was so embarrassing. And when I got my first job, he rang up my employer to say that I was getting abuse in this capitalist society. And I was horrified. And how could they take advantage of me. and I was in my first job. So my efforts to integrate were really interfered with. Not out of a bad place but it was like that. And in a way, my individual family unit was quite isolated from the wider family. So you had these kind of failures of facilitation going on. To facilitate that social chi to flow well. So I became in that sense an outlier. But I didn’t realise it. Because I had good social skills so I could engage with that? But in a way there was a kind of wound from that time I’ve never really healed. And it explains in a way why in many of these social things I’ve burned out. So I do these things, and they get recognised and they're really great. But I tend to carry a lot of it, and I'm still doing that. And I’ve done I think as much as I can in terms of, you know, working with my mind. I can manage my state really well, but there’s a problem if the deeper story that you're living is that you are effectively isolated. So even with people. It’s subtle, because I, you know, from the South American side, the social side, it really flows. I feel fantastic, you know, with people and I won't feel like an odd one out in a party, necessarily. I can have the sort of wild thing and get into the spirit really well. But that wound is still there in some ways. And I thought well what’s the solution?

And I was thinking well, because I’ve done this other thing where I’ve kind of gone back to times in my life and I’ve created an alternative history for that time and I sort of think of energising that time. Because then my identity about myself shifts, because it’s like energising the past, if you see what I mean. But that is still there. And I know that there are many other people who haven’t had sort of healthy facilitation into society. And this isn’t just a wealth thing, this is much more about the emotional set up of a whole community. Economics does play a role, and migration, all sorts of things do play a role, demographics. But essentially, the underlying pattern is that those wider family, your ideal wider family, never found them. So I thought, what if you could then actually really connect and think who would that be? Who are the people that could be a surrogate aunt, a surrogate uncle, a surrogate mother, father? I know my Mum wouldn’t mind, I got told that. And who I could develop a sort of relationship where I'm the mentee. So it could be coaching, it could be just listening, it could be just cups of tea. But base this connection to plug in for people who never got plugged in so that the social chi flows. Sort of do everything else, but it’s like that would overcome structurally that isolation. And a wound. So that, I was sort of thinking about over the last few days and I was thinking I’d love to do that for myself. And then I’d love to sort of help people in my family do that for them. Yeah. It was just –

Bushra: It’s amazing.

Sofia: You know because we talk about intentional community? This is intentional family, but not the nuclear unit. It’s intentional, the family integrated into society thing. There’s something about bringing it home. There are few families that have had very functional families but most people have something in their life they need to work with, you know.

Bushra: But do you think, like we automatically look for someone to substitute the dysfunctional relationship? You know, we do it anyway. And sometimes we just get another dysfunctional relationship.

Sofia: Yeah.

Bushra: And sometimes we get someone who is very healing. Either way they're on that spectrum of … we’re looking –

Sofia: I see what you mean. Oh God, yeah. I think that we so, you know, people come into our lives so much based on kind of … Sometimes what we consciously ask for, sometimes. But mostly what we unconsciously are kind of asking for. You know what I mean.

Bushra: Sometimes on paper there are people that you should get on with.

Sofia: Yeah. Yes, that’s a really –

Bushra: And on paper there are other people that, like, no-one would ever see you guys. I'm not talking about boyfriends, but just even, you know, friends. And actually you speak to them and you feel a connection which is so deep. And you don’t know how, like, where did that … Even now I meet people like that and I just think, you know … Where is that essence? Why? It doesn’t make … In some ways you don’t care it doesn’t make rational sense.

Sofia: It’s amazing. Yeah.

Bushra: You're just happy that it it’s there and it feels more real than something, you know, than gravity, for instance, we’re talking about.

Sofia: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Bushra: And it changes the way you feel about yourself as well.

Sofia: God, yeah. Yeah.

Bushra: You know, that kind of, that sense of self. It does, all of a sudden you think yeah, I did have a … I know I’ve got cracks in my personality or my being. And you look for things to put a plaster over them, that never work. And then you sometimes have a conversation or someone comes into your life and … well, it does heal. It doesn’t heal everything, but it does … Like the burden is gone and you don’t really know why other than some connection or understanding or soul mateyness or whatever it is.

Sofia: Yeah.

Sofia Bustamante The Beats

Sofia: So one other thing I got into was going, kind of on the trail of where stories had emerged from. I did one in Germany on the trail of the Brothers Grimm. I went to where the Grimm fairy tales come from with a group of people and we’d travel around in a van, that we called the Fairytale Mobile and we’d go into the forest and we’d look for an oak tree, for example, and we’d tell stories under the oak tree relating to that area. And we got someone local who basically was a fairy story teller. And we’d sort of relate that to things we were going through in life. It was just very beautiful and it was to connect an area with the psyche of a country with its time actually.

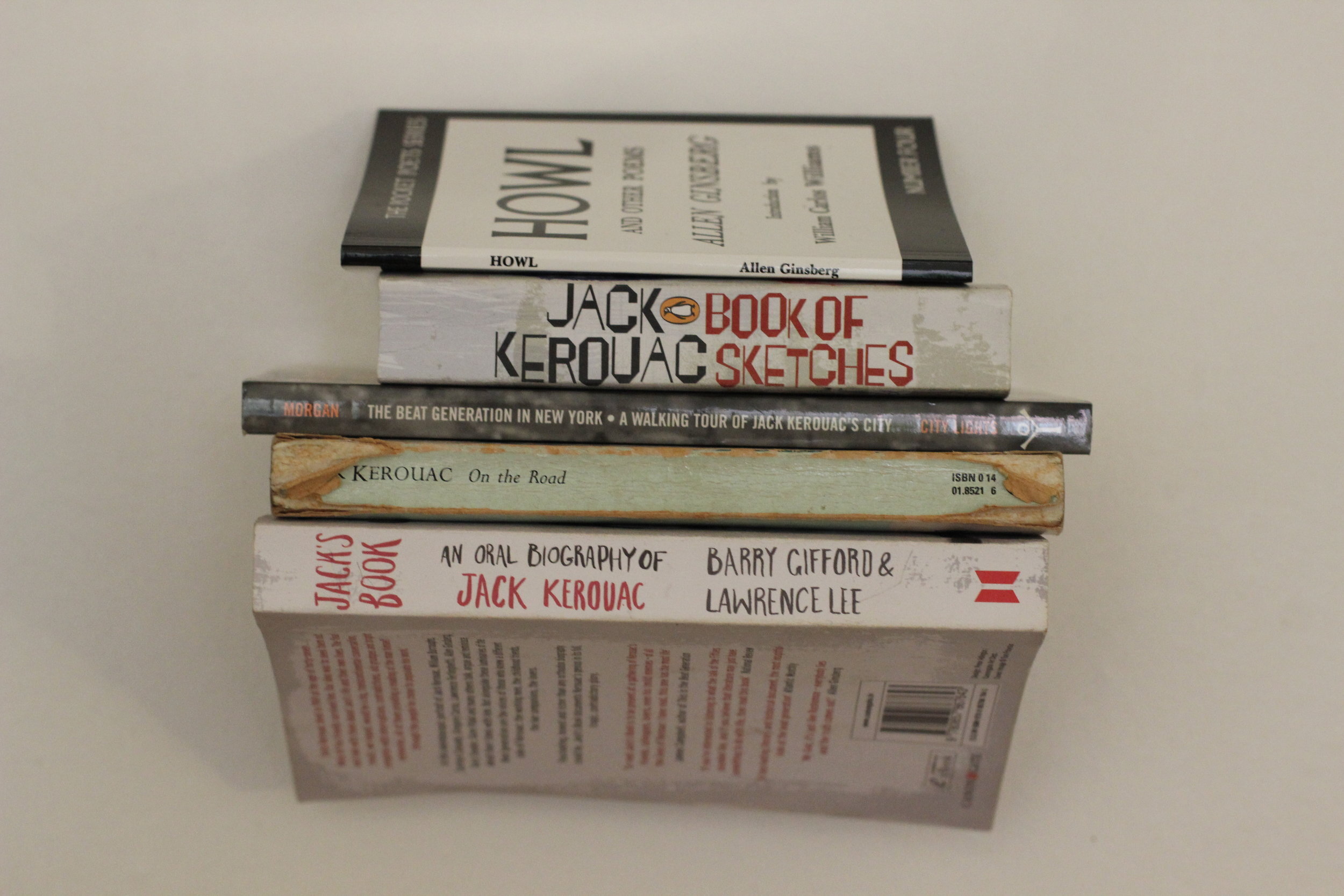

Then I wanted to kind of get under the skin of The Beats. So we did this thing of going on the trail of The Beats. And we went to New York and also to San Francisco. And yeah, I just sort of found the cafés where they made to sit, and read material from The Beats there. I went to the city bookstore. It was funny, I was in one café and got talking to someone. She said oh, do you know who that is over there? And I said no, and she said oh, that’s Lawrence Ferlinghetti. And Lawrence Ferlinghetti was the guy of the City Lights Bookstore that published that poem, Howl. And there he was. And I wanted go up and say hi. It took me a while to muster up the courage, because, you know, it’s that typical thing of what am I going to say? And I thought, you know what, he’s just a human being like me. I'm going to go over and say hello. And I went over and he’d gone. It was one of those lessons in life. you’ve got to just take the moment.

I came across The Beats when I was 20. And I picked up a copy of On The Road. I don’t know how it came into my hands. And I started reading it and I couldn’t understand a thing. It was this fifties American slang. And at first I couldn’t get into it at all. But I’d heard of it and I wanted to read it. Because I’d sort of come across, not The Beatles, the sixties, the sort of counterculture movement the sixties started. Obviously I wasn’t around then, but in the seventies when I was just transitioning from my early years to teenagers, you know. Early eighties actually, rather. I just was hearing these broadcasts on the radio about the sixties and about how they were recording people saying don’t go to school. Question everything, you know? That was so interesting for me. So the sixties and of course the fashion and the imagery and the spirit of it really grabbed me. It’s amazing. And I wished I’d lived in that era.

I’d heard about The Beats but didn’t really know what they were, and I came across this book, couldn’t get into it, and then I picked it up a bit later and I just couldn’t put it down. This feeling of this spirit really, of sort of searching for something and really raw and real and honest in its writing. And I just felt like I was there on this trip, like all the trips that he was doing. And all these mad, creative characters that were pushing things to the edges, at the time when it wasn’t … not everybody was doing that. Because in the sixties everybody was now questioning things, doing what they want openly. In the fifties it wasn’t like that at all. Especially for women. Actually, men got to live that a bit more, as women, if they rebelled would sooner actually … It was said that they belonged to their parents first and then their husbands. And so it would be often the parents that would basically section them. If women rebelled too much they could get electric shock treatment. So it was really, really oppressive for women. Also for men, they’d get ridiculed and ostracised and it wouldn’t be easy at all. I had a lot of respect for those artists, basically.

And afterwards I found out more what they were about, what they were for. Because reading On The Road was really just the spirit of it, and it touched something but I just couldn’t articulate what it was. And later I sort of realised that they were articulating a really deep sort of existential pain that they were feeling, that the country actually was feeling. Because we’d had the war and, you know, there was the Cold War of course. But out of that period of the Second World War, then there was this, like, where are we going? And in America, they had a sense that America was moving in a certain direction. And they were really questioning it. I’ve got the T-shirt, I don’t know if I’ve shared this with you before but I’ve got a T-shirt and on the back it’s this kind of road sign, and it says “wither goes thou America with thy shining car at night”. It really encompassed what they were standing for. And they were really well read. Sort of self-educated, they’d often dropped out of things and informed themselves on a whole pile of different things. So they weren’t like … What was often thought of them as they weren’t bums, you know? They were daring to question things. And then they had their own sort of rituals, like they were into drugs and actually really believed in it as a form of taking yourself to having altered experiences and being able to see the world in different ways.

And then this poetic prose of Jack Kerouac was about writing from your own experience as is now. And as an art form. So not editing, so not interfering with it. Just writing from your being place. So that I found amazing and wonderful. I just love the Beat poetry. Kerouac and Ginsberg. And then there’s Howl. So Howl, Allen Ginsberg was one of them, one of The Beats, and he shared this poem, Howl, which was a kind of clarion call to the artists and challenging them, speaking to them as well. And he was just amazing. I still listen to it and it’s incredible, it’s so, so rich. And it got published. Yeah. And then censored and this court case and they won the court case and they argued … trying so say it was obscene, which it was for the time. But for The Beats it was honesty. It was like, blues, for me, is such an honest form of music. I love the blues. It articulates the difficult feelings really that are not commonly experienced, understood and articulated in that sort of raw way, and I really, really love it for that. So The Beats I saw in a similar way. There are times in my life when I’ve been with cultural creatives and it feels like we’ve been … there’s that feeling of enough people that question things, when you get enough people that question things together, you just really open up a different possibility of seeing the world in different ways, as a habit, you know. You've just got to be careful not to surround yourself too much with those people all the time because you become weirder than you think.

Bushra: How do you think it’s formed your … At the time how did affect your view of the future?

Sofia: In just that one broadcast I heard that said question everything and don’t go to school. You know, that thing of someone, with a kind of authoritative voice saying don’t go to school, really made me question … well if you can question school, what can't you question? And my parents were in many ways quite bohemian anyway, underneath things. So I felt like my mind could go anywhere, you know. And for a while it was tied into just looking, only taking hard science really, but my own questioning was really alive. And my question really was about the inner world. About the things that, you know, I like The Beat poetry because it was articulating the unseen. And it articulated in a way how things were moving pre the counterculture movement. And it nudged it. I mean for example, The Doors said they wouldn’t have been The Doors without The Beats. There were so many rock stars that we know that were influenced by them, it’s not funny, really. Bob Dylan, you know, so many people.

So, I felt like we could question anything. And what I felt was missing, you know, in my experience of life, was an articulation of the unseen. Particularly the emotional world. Because there was something in it that made sense to me. So for example, the blues music articulated that. Gave voice to it. The Beats would give voice to the people’s experience and that helps in a way, that would help to see what’s there and then be able to make sense of it. Because I felt like there’s a reason for every single thing that we experience and feel there’s a reason for it. So there isn’t such a thing as being illogical, because at some level there is a logic to what anyone says it does. You just have to get to the right level and world view and context that they're in and it makes sense. So people do actually make sense. We just don’t have the explanation for it, necessarily.

And partly because, you know, our society’s based on the machine way of doing things, the machine view of life. That we can control nature and dominate it, and we can put everything back into an orderly fashion, you know. And it was the feeling that that’s not really the case, I need to question that and then Fritjof Capra’s work really influenced me. Looking at living systems and tying up different areas of life. Again making sense, you know, and connecting up the patterns, between in his case in one of his books, economy, consciousness and society. And drawing the parallels. And that was really exciting for me. Because there was this feeling that there has to be a reason, there is a reason for things. And we might not know it yet but I really felt that, there’s a reason for things. There’s a reason for everything. And in my lifetime I might not get to know it all, and as society progresses science slowly articulates the reason for things, if you like. So thanks to … Actually, in a way getting some back up. Some material that gave evidence …So luckily, in my twenties some books came out that helped to give some hard evidence to all of this stuff and for example, Fritjof Capra was one of them. Daniel Goldman was another who brought out Emotional Intelligence in 1985. And that was just amazing. Because you know, it really, really did give something that I could work with and develop some explanations as to why we can organise things differently, for example. And then in terms of the emotions why it’s important to vocalise them and understand them and get underneath them and understand what message they're bringing all the time. And that then led me gradually, because I got involved with the networks where I could practice this stuff and really get my hands dirty and experiment a lot. So basically between sort 25 and 35 I experimented a lot with running things that worked to design interactions and experiences because of understanding in a way the patterns of these unseen things. The inner our self. And then the living systems, which explains much better why groups behave in the way they do and how we can create different experiences in groups. And if you imagine that’s to do with creativity, that’s do to with conflict, that’s to do with purpose, purpose of a group and purpose of an individual. So all this stuff that seemed like really soft and people just don’t do that stuff, they just can't deal with it, actually they could kind of engineer it. So we talk about technology all the time but then I talk about … I had to find a way for this stuff to be taken seriously. We were in a science place, and I know, I knew and understood and I’d seen the scepticism right up front about all these unseen things. So there was at university an engineering course, in one of the top universities in the world, with very high performing people, having these incredibly deep questions about life and knowing that the mainstream did not have the answers, and openly questioning them. You know, in front of my engineering colleagues and being –

Sofia: - in the nicest possible way, brutalised. Yeah. But knowing and sticking to my guns and little by little finding out actually, why it does make sense, why this stuff really does make sense. And Candace Pert when she wrote Molecules Of Emotion, it was just so fantastic because it was another … these things were not bibles, but encyclopaedias, like compendiums that had undeniable facts that actually forced people to take this stuff seriously, you know.

And then you know, gradually, the notion of emotional intelligence was coming out and the notion of living systems very gradually. Now a lot of people recognise open space, you know, as a process. In those days a lot less people did. Open space, that process where you run things as though the whole event actually is a coffee pause. It’s run from that ethos that nobody does anything, nothing ever gets done unless someone steps forward with passion and with responsibility for their passion. And so the event is set up to invite that into a centre. To invite people to step forward and then with self organisation, people self organise around the passion and purpose. So those processes that enable, in a way, human emotion and natural impetus to drive things, they don’t have to fake buy in. All these company brochures that need people to get buying and everything. Actually, if you run it all from where, you know, the stranger trapped in the middle, the kind of the impetus being people’s purpose and motivation, then none of that has to be done. So to take that seriously and have a method to be in touch with that and to encourage it and to nurture it and to just work with it as a reality just means that you get much better functioning organisations. For example, an organisation I came across called What If. And I really liked how they had, for example, they had the revolution team and they recognised that you couldn’t just take a small aspect of people and employ that part of them. They recognise that the whole person was important. And they really were quite progressive in developing a culture where that would be part of the reality of it. And so they were early on in having these places and spaces where all the wealth of human emotion was brought into the workplace and channelled, like creativity is channelled, they capture people’s feelings, those different places.

Bushra: Also with the work that you’ve done, did you –

Sofia: Yeah. Sure. So what I did with London Creative Labs … Well, OK, I guess there’s one story that’s kind of key. I was in Geneva and by that point I’d got, you know, how can I say, I’d got professional respect for working with these processes and actually bringing them into the mainstream. And you know, I’d use the word they're social technologies, which they are, and I sort of realised that people didn’t see them unless they were in the form of an object. So although these things are processes, I had to describe them as an object for people to actually see them. So, so long as I gave a name to any process I was doing and called it a thing, people would pay for it. Even though the thing was just one random instance of a process. I created this thing called Social Start Up Labs and Skills Camps that enabled a local community to tap into a lot more of the local talent. Basically I wanted to prove a hypothesis which is that when you include more people in the local economy, it becomes richer and more diverse. Sorry, if you include diversity in the economy you get a better economy, you get a stronger local economy by a factor of ten. And to do that I just had to find ways to include people into that process and so I designed a process that would do that, like the Social Start Up Labs brings everyone in the local area and has an intensely designed process over a day. No-one believes it at the beginning and everyone’s amazed at the end, because we’ve basically mapped all the assets in the community and people have actually got to understand what an asset is. So it’s not just, say, an empty building, an asset is a coded piece of information. It’s the thing, it’s like who has access to it? How its benefit can be unlocked. The different kinds of uses. And all the different things that would make that thing actually come into a living being. You know, a live asset. And people, everybody were sort of like handling individually this data that was theirs of their own local community. And we mapped it and they got a picture.

Sofia Bustamante Profile and own thoughts

award winning social innovator and thinkerer

Future Visions:

If mankind survives this century, we will see more and more technology that does not just imitate nature but actively evolves it.

We will have much better maps between inner states and outer dynamics. Consider the Pixar Movie Inside Out. Technology will assist in this process. What are considered “Sidhis” will be more easily attainable through the aid of technology to train these abilities and also to map our inner worlds to outer practices.

We will better understand abilities such as those of sensing across distance telepathy and empathy… Consider Sense8 - series by Wachowskis in which these skills actually demarcate a break in species.

Identity maps will emerge, portraying a much more sophisticated picture of who we are.

A post-work society which has successfully address the issue of distribution of resources, will allow more emphasis on the non material qualities of life. There will be rapid acceleration of meaning as a strange attractor in our lives. Identity will be understood in ways that go beyond an individual and start to show that we are not in fact separate but different versions of ourselves and each other.

Our experience of time will change, as our values and perception. We will free our past and create alternative histories which do not deny trauma but resolve it, and integrate the wisdom and learning, influence our current identity and better recognise when time, and the past is used as an abstraction to deflect us from our soul purpose.